Use the microscope to take a careful look at the spaces between the floc particles. Are there any long, hair-like organisms projecting out of the floc particles? These are filamentous bacteria. Believe it or not, filamentous bacteria of this type are some of the oldest microbes on our planet and have survived unchanged for millions of years. This makes these types of bacteria able to adapt to many different environments and fill many niches where other life forms cannot survive.

When these filaments are present in the right amount in mixed liquor, they form the “backbone” of the floc particles, which adds strength and density to the floc. However, when these filamentous bacteria grow too numerous, they tend to keep the floc particles from being able to come together. This is the result of the shape of the filaments themselves, which act like the fibers in fiberglass house insulation, which maintains the “loft” that provides the insulation layer. If enough filamentous bacteria are present, they can actually prevent any settling and solids separation for occurring. When this phenomenon occurs in mixed liquor, the sludge is said to be “bulking”.

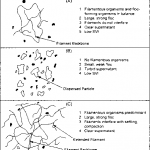

When viewing filamentous bulking using a light microscope, the filaments will sometimes be seen inside the floc particles themselves. When this occurs, the floc becomes expanded and cannot settle. This is known as an “open” floc structure. In other instances, the filamentous bacteria will extend from one floc particle to another. This is known as filamentous “inter-floc bridging”. Bridging of this type can result in the worst sludge bulking episodes. If no action is taken, serious bulking can lead to solids washout in the secondary clarifiers, resulting in permit violation and environmental impacts.

Filamentous bacteria can also be responsible for foaming problems. Typically, activated sludge foaming problems are related to the amount of fats, oils and grease that a facility receives. In general, wastewater plant that receive large amounts of fats, oils and grease experience foaming problems at least once or twice per year. Sometimes the problem is continuous. Plants that do not have adequate pretreatment facilities (barscreen) also experience foaming problems. These foaming problems result from filamentous bacteria that survive on the grease and oil that floats on the surface of aeration basins. Some types of filamentous bacteria have evolved to become buoyant. In this way, they alone are in contact with the fats and grease that they use as food. When a large slug of grease enters the aeration basin, these organisms quickly break down the grease, which results in the formation of a foam layer.

Beyond the numbers of filamentous bacteria and whether they occur within the floc itself, in inter-floc bridging or in foam, you can observe the type of filamentous bacteria that you are dealing with using a microscope. However, identifying different types of filaments can be time consuming and difficult. Furthermore, a specialized type of light microscope, known as a phase-contrast microscope is used for this type of work. When the type of filamentous bacteria responsible for a bulking episode can be identified, the cause of the over proliferation of the filaments can often be understood.

Filamentous bacteria identification and the conditions that lead to the growth of different types of filamentous bacteria is discussed in great detail in the Manual on the Causes and Control of Activated Sludge Bulking and Foaming, 3rd edition., by David Jenkins, Michael G. Richard and Glen T. Daigger. As this manual explains, filamentous bacteria are classified under a system that gives some of the bacteria actual names and identifies others using numbers.